June 6th, 2024 | by Keaton Smith

I had known that plastic wasn’t great for you for a while. I tried not to microwave my food in plastic, opted for my wooden reusable utensil set over a disposable fork, and avoided disposable plastic bottles.

But I was fuzzy on the details. Wait, what is plastic supposed to do to me again? What exactly is bad about it? How big of a deal is this issue?

A few months ago, we started seeing more and more news articles about micro and nanoplastics, prompted by the release of a big study from Columbia University. This study found some scary stats about the sheer number of nanoplastics in plastic water bottles.

Carina, Robby and others on the team knew a lot more than me– at the time, I had only recently started at Bivo and was still getting up to speed on the science of plastic.

But, still, I wanted to get some things straight, and I figured I couldn’t be the only one still with some basic questions. So, I sought out an expert to answer some of the most common questions we see about micro and nanoplastics.

For today’s post, I interviewed Rachael Z. Miller, a friend of Bivo (Peter’s high school sailing coach!) and a microplastic expert.

Rachael is a National Geographic Explorer and the founder of the Rozalia Project, a non-profit that tackles the problem of marine debris–which includes waste like old fishing gear, consumer debris and microplastic and microfiber pollution. They conduct research from a 60ft sailing research vessel and use actual underwater robots to pick up samples from the ocean floor.

Throughout our chat, Rachael really helped me get a better sense of the scope of the issue. Thanks, Rachael!

I had known that plastic wasn’t great for you for a while. I tried not to microwave my food in plastic, opted for my wooden reusable utensil set over a disposable fork, and avoided disposable plastic bottles.

But I was fuzzy on the details. Wait, what is plastic supposed to do to me again? What exactly is bad about it? How big of a deal is this issue?

A few months ago, we started seeing more and more news articles about micro and nanoplastics, prompted by the release of a big study from Columbia University. This study found some scary stats about the sheer number of nanoplastics in plastic water bottles.

Carina, Robby and others on the team knew a lot more than me– at the time, I had only recently started at Bivo and was still getting up to speed on the science of plastic.

But, still, I wanted to get some things straight, and I figured I couldn’t be the only one still with some basic questions. So, I sought out an expert to answer some of the most common questions we see about micro and nanoplastics.

For today’s post, I interviewed Rachael Z. Miller, a friend of Bivo (Peter’s high school sailing coach!) and a microplastic expert.

Rachael is a National Geographic Explorer and the founder of the Rozalia Project, a non-profit that tackles the problem of marine debris–which includes waste like old fishing gear, consumer debris and microplastic and microfiber pollution. They conduct research from a 60ft sailing research vessel and use actual underwater robots to pick up samples from the ocean floor.

Throughout our chat, Rachael really helped me get a better sense of the scope of the issue. Thanks, Rachael!

Microplastics are plastic particles that measure between 5mm (half the size of your pinkie nail) and 1 micron. They include pieces intentionally manufactured at a small scale (like face glitter) as well as pieces that are fragments of larger plastic items.

Synthetic microfibers are included in the umbrella of microplastics. Microfibers, in general, are tiny fibers that have broken off of longer fibers. While these microfibers can be non-synthetic (natural), many are synthetic (made from plastic) and most are treated with chemicals (think: fabric softener and dye-setting agents) that would be harmful to humans and the environment.

Nanoplastics are even smaller. One micron and smaller. (For reference, 70 microns is about the width of a strand of hair, so nanoplastics are waysmaller than that).

Scientists are only just starting to publish studies on nanoplastics so the research is limited- mostly because the technology available to study something this small is so new that it isn’t widely used yet.

Microplastics are plastic particles that measure between 5mm (half the size of your pinkie nail) and 1 micron. They include pieces intentionally manufactured at a small scale (like face glitter) as well as pieces that are fragments of larger plastic items.

Synthetic microfibers are included in the umbrella of microplastics. Microfibers, in general, are tiny fibers that have broken off of longer fibers. While these microfibers can be non-synthetic (natural), many are synthetic (made from plastic) and most are treated with chemicals (think: fabric softener and dye-setting agents) that would be harmful to humans and the environment.

Nanoplastics are even smaller. One micron and smaller. (For reference, 70 microns is about the width of a strand of hair, so nanoplastics are waysmaller than that).

Scientists are only just starting to publish studies on nanoplastics so the research is limited- mostly because the technology available to study something this small is so new that it isn’t widely used yet.

Unfortunately, they are everywhere. In the ocean, on the hiking trails, in the dust in your house. They’re even in remote parts of the world. Rachael and her team found microplastics, mostly microfibers, in the Southern Ocean, the Falkland Islands, and the Antarctic Peninsula.

Unfortunately, they are everywhere. In the ocean, on the hiking trails, in the dust in your house. They’re even in remote parts of the world. Rachael and her team found microplastics, mostly microfibers, in the Southern Ocean, the Falkland Islands, and the Antarctic Peninsula.

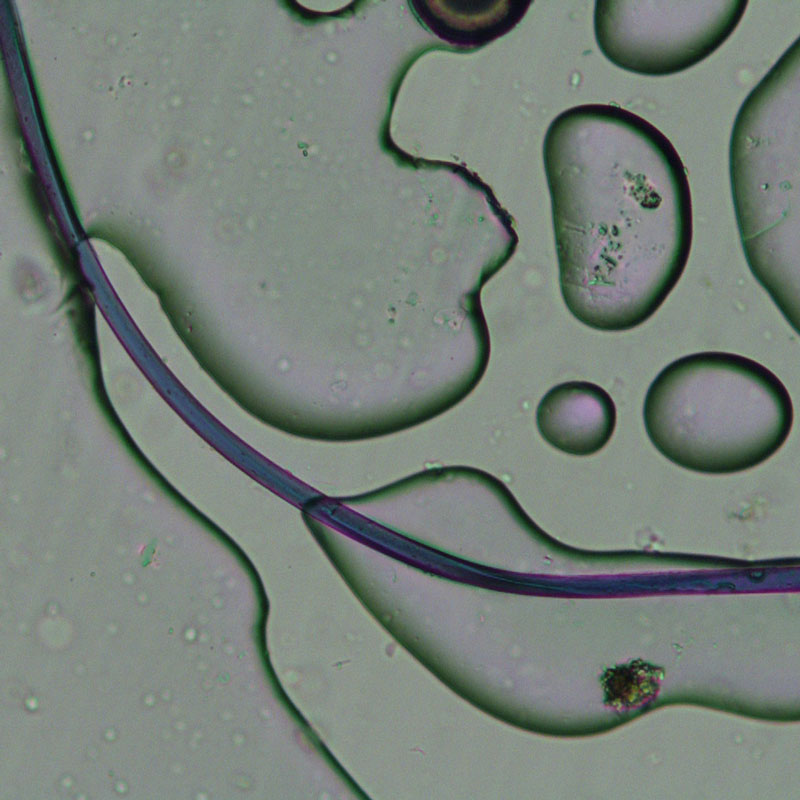

Left:The team from Rozalia Project for a Clean Ocean conducting microplastic research in the Hudson River to both understand and prevent the problem.

Right:A blue polyester fiber found in the Hudson River.

Left:The team from Rozalia Project for a Clean Ocean conducting microplastic research in the Hudson River to both understand and prevent the problem.

Right:A blue polyester fiber found in the Hudson River.

Plastics are known endocrine disruptors, meaning they wreck or mess with reproductive systems. Additives associated with plastic manufacturing can also cause harm to living creatures. While the majority of studies from the last 15 years have been focused on establishing myriad harms that microplastics can cause to creatures in and around the water, it has only been over the last few years that studies to understand the implications for humans have surfaced.

Recent studies published in March of this year (here and here) have established correlations (not causations, but still enough to give us a scare) between the presence of microplastic in various parts of the human body, including everything from behavior change to disrupted gut biome, reduced fertility and even heart attack, stroke and death.

While to date, there’s no ‘patient zero’ that establishes a causal link between microplastics and a particular issue, for Rachael, at least, the evidence to reduce exposure to plastic is extremely compelling.

Plastics are known endocrine disruptors, meaning they wreck or mess with reproductive systems. Additives associated with plastic manufacturing can also cause harm to living creatures. While the majority of studies from the last 15 years have been focused on establishing myriad harms that microplastics can cause to creatures in and around the water, it has only been over the last few years that studies to understand the implications for humans have surfaced.

Recent studies published in March of this year (here and here) have established correlations (not causations, but still enough to give us a scare) between the presence of microplastic in various parts of the human body, including everything from behavior change to disrupted gut biome, reduced fertility and even heart attack, stroke and death.

While to date, there’s no ‘patient zero’ that establishes a causal link between microplastics and a particular issue, for Rachael, at least, the evidence to reduce exposure to plastic is extremely compelling.

Finally, there are many steps we can take in our own lives to reduce our own exposure to microplastics. While the issue may be more on a systemic level, here are some tips to think about moving forward:

To help slow the spread of microplastics, there are lots of small things you and I can do.

One way that microplastics and microfibers enter the waterway is via washing machines. Microfibers shed off of the clothing being washed and exit the machine along with the water, entering the local waterway and making its way to the ocean. Rachael shared some tips on reducing this shedding:

Finally, there are many steps we can take in our own lives to reduce our own exposure to microplastics. While the issue may be more on a systemic level, here are some tips to think about moving forward:

To help slow the spread of microplastics, there are lots of small things you and I can do.

One way that microplastics and microfibers enter the waterway is via washing machines. Microfibers shed off of the clothing being washed and exit the machine along with the water, entering the local waterway and making its way to the ocean. Rachael shared some tips on reducing this shedding:

A bundle of microfiber filtered from a load of winter laundry done in a top-loading washing machine. While most waste water treatment plants are able to stop the vast majority of the fibers that arrive in the influent, it is likely that fibers like these can still end up on our public waterways as part of fertilizer.

A better solution is to prevent this from happening in the first place with more resilient clothing, better washing settings and techniques and through the use of in-drum, in-line or external filtering devices.

A bundle of microfiber filtered from a load of winter laundry done in a top-loading washing machine. While most waste water treatment plants are able to stop the vast majority of the fibers that arrive in the influent, it is likely that fibers like these can still end up on our public waterways as part of fertilizer.

A better solution is to prevent this from happening in the first place with more resilient clothing, better washing settings and techniques and through the use of in-drum, in-line or external filtering devices.

Another way that microfibers shed is just when we wear our clothing. Rachael suggests strategizing around what we’re wearing:

My talk with Rachael certainly gave me a lot to think about and I hope this has helped you all a bit more. What additional questions do you have? Ask them in the comments or write us (thirsty@drinkbivo.com) and we’ll work on getting answers for you! Cheers, Keaton

Another way that microfibers shed is just when we wear our clothing. Rachael suggests strategizing around what we’re wearing:

My talk with Rachael certainly gave me a lot to think about and I hope this has helped you all a bit more. What additional questions do you have? Ask them in the comments or write us (thirsty@drinkbivo.com) and we’ll work on getting answers for you! Cheers, Keaton

Today in our Quench’d series, we are hearing a story from SMS Nordic coach Alex Jospe, a recent recipient of the National Nordic Foundation's Trail to Gold Fellowship. The fellowship is awarded to talented women ski coaches across the US, and gives them an immersive trip into all aspects of World Cup coaching and ski waxing. Read about Alex's life changing trip!

Wondering where to bike on your trip to Bentonville, Arkansas? We have compiled the best mountain bike rides near Bentonville to make sure your trip is a success. Plus, where to get coffee, lunch, and bring the kids after your ride.

For Quench'd this week, we interviewed adaptive athletes Allie Bianchi and Greg Durso as well as advocate Berne Brody about the release of their new film Best Day Ever, highlighting Vermont's newest bike park built entirely for adaptive riders.